|

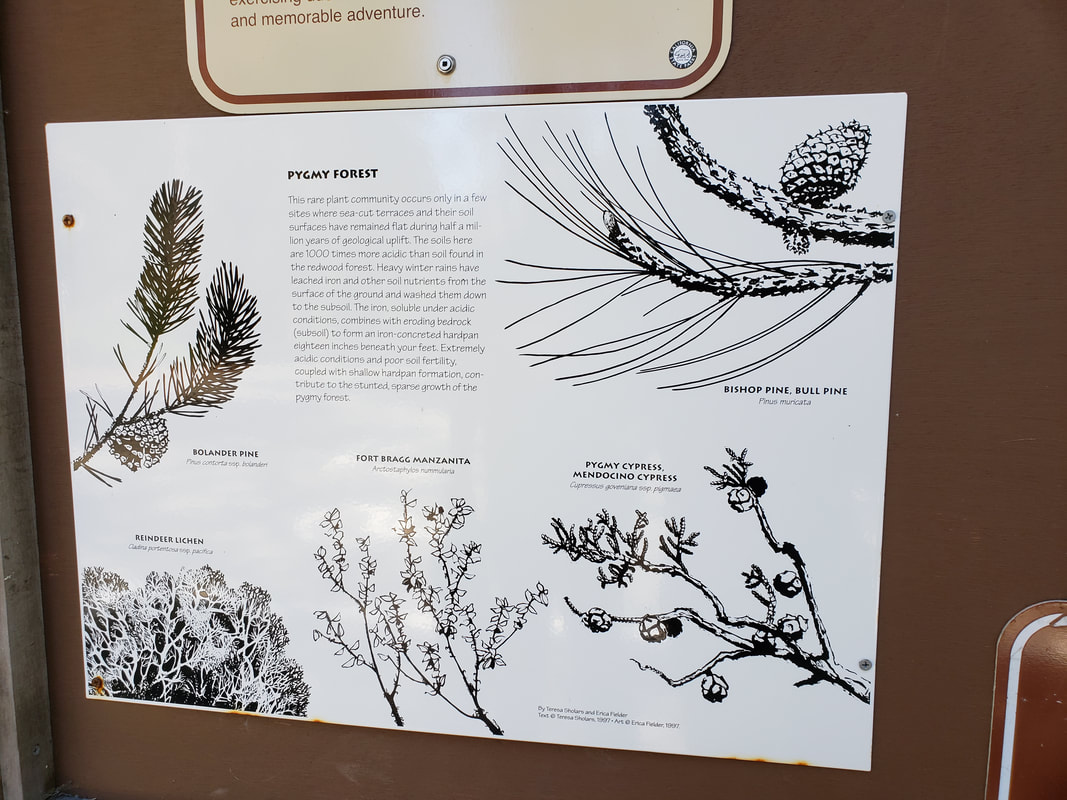

Recently, I had a chance to visit the Pygmy Forest in Mendocino. For my fellow geography buffs, it is about 2-3 hours north of San Francisco, close to the coastline along Highway 1, and just south of Fort Braggs. The Pygmy Forest is over one hundred years old and filled with trees that are hardly taller than you and me. Just a stone’s throw away are these colossal redwood trees which in comparison clamber into the sky. As I scanned along this tree line and smelled the sea seasoned air surrounding both forests, I could not pinpoint anything that could conceivably cause such a drastic height different. Intrigued I decided to dig a little deeper and read the signage at the trailhead pictured below: Pygmy Forest: This rare plant community occurs only in a few sites where sea-cut terraces and their soil surfaces have remained flat during a half million years of geological uplift. The soils here are 1,000 times more acidic than soil found in the redwood forest. Heavy winter rains have leached iron and other soil nutrients from the surface of the ground and washed them down to the subsoil. The iron, soluble under acidic conditions, combines with eroding bedrock (subsoil) to form an iron-concentrated hardpan 18 inches beneath your feet. Extremely acidic conditions and poor soil fertility, coupled with shallow hardpan formation, contribute to the stunted, spare growth of the pygmy forest. For whatever reason, this unique landscape could not escape my mind and reminded me of a dichotomy seen elsewhere. A dichotomy I had seen walking the streets and neighborhoods of San Francisco. A dichotomy I had seen crossing under and overpasses in Silicon Valley. A dichotomy I had seen flying and roaming the heartland of the United States. This was not limited to differences in melanin, but rather differences in incomes with a growing inequity. A dubious dichotomy whose tentacles extend into classrooms, schools, and American Dreams. A difference that has manifested in the contrasting legacy of Nairobi College to that of Stanford University. A difference that I have a difficult time explaining. Similar to geography, the inequities in education piqued my interest. At first, it was a simple reflection of my experience within education and comparing and contrasting it to that of my peers. But there were a few concerning patterns I noticed which I decided to explore it further after graduating from UC Berkeley. Like any good Berkeley graduate, I approached it with an academic rigor reading academic articles, books, and attending lectures. While I learned a lot, there was no way to succinctly describe the problems I saw and what I believe. Well that is, until now. After some reflection, I concluded that the pygmy forest is the perfect analogy for the American education system. How? Well, it is important to first recognize that the current American education system did not spring up overnight. It has developed over time, and the “achievement gaps” we see today are a result of lapsed time and frankly, bad policy. While some communities and areas were uplifted by the system, others were ignored. As a result of these decisions, positive feedback loops were created for both communities with very divergent outcomes. On one side, the soil is rich and fertile, allowing the redwood trees to reach great heights. On the other, the soil in the pygmy forest was systematically stripped of nutrients and resources, resulting in poor and inhospitable conditions which indiscriminately restricted the growth and thus height potential of each tree in that region. Please note the pygmy tree adjacent to me and the redwood trees in the distance. No scientist, or any sane and rational person really, would look at the trees in the pygmy forest and claim, “The reason that you, pygmy tree, are not growing as tall as the redwood tree is because you are not as smart, intelligent, driven, talented, or gifted as those redwood trees.” In this context, it is laughable. So why then is it deemed remotely reasonable when this same “logic” is applied to students? It is absurd. It does not consider students environment, context, and experiences and takes a singular approach to what is obviously an extremely complex multifaceted issue. Instead, what we ought to do is question everything and dare I say—dig a little deeper. Some questions that come to mind are: Is height in fact a fair metric of comparison for pygmy and redwood trees? If not, what is? In schools, academic success and “intelligence” are measured by grades, test scores, IQ, SAT scores, etc.—are these fair metrics of comparison? If not, what are? Better yet, why do we even need metrics of comparison? What value do they add? Are they indicative of intrinsic characteristics? If not, what impact and or unintended consequences could stem from attributing a lack of growth to a supposed inherent flaw? Are we doing more harm than good by using metrics? Are we measuring what matters? What can we do to redefine success so that it is no longer based on your roots? If there is a problem, what can we do to reshape the environment? What policy level changes can we make to address the “achievement gaps”? Can we create an environment where all trees and students can reach their potential, whatever that may mean to them? What are our responsibilities and obligations as members of this ecosystem and society to these trees and students? More importantly, what can we do to fulfill them? This is just a brief window to my brain at 3:00 AM. Furthermore, how can we encourage a positive learning environment for our students? Several plant studies have demonstrated that positive affirmations and encouragements boost plant growth while negative statements and condemnations stunt it. Humans are also living breathing beings who feel as well—can you imagine how negativity impacts us? Fortunately, we have some answers to a few of those questions. Claude M. Steele is a well-renown social psychologist explores some of these issues in his book Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. While there is no denying that we live in a society filled with stereotypes, his analysis reveals that these biases can be internalized and result in real tangible impacts that can be both positive and negative. The language we use has an impact, but fortunately there are ways in which we can mitigate the impact. Another book that addresses some of the aforementioned questions is Ungifted: Intelligence Redefine by Scott Barry Kaufman which brings to question how we measure intelligence or success and explore the unintended consequences of creating false binaries. That being said, academic success, perceived intelligence and even wealth bode no relationship with whether or not a person is ethical, moral, or generally lives a happy life—I am sure you can find several examples within your own life or on the news to support this claim. Last time I checked, you and me, we are not trees and therefore are not limited to and deeply rooted in the environment in which we were brought up. We have feet, we have hands, we have eyes, and hopefully, we have some ability to think (or some variation of the aforementioned). More importantly, we have the ability to change the environment around us. It might be a herculean task, and we may not be able to change things single-handedly. But if we cannot do it alone, we sure as hell can do it together. We can roll up our sleeves to reshape the environment and reshape our environment into one where everyone can thrive and be uplifted. That vision is something my team and I care deeply about at Major Probs and are actively working to address. Call me naïve, but I truly believe that we can and need to change things, but before we do that we need to dig a little deeper. This photo was not taken at the Pygmy Forest, but rather the Glass Beach in Fort Braggs. It is representative of the choices we have in life.

0 Comments

|